Journey Among Women, 1977 (Tom Cowan, dir. and John Weiley prod.) screend as part of a retrospective of Australian feature films, Film Continent Australia, at the Film Museum, Vienna, April 4 to June 4, 2019.

|

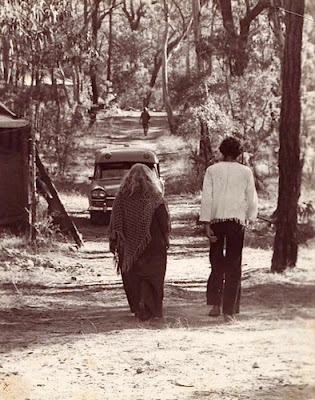

| Nell Campbell, Robyn Moase, Theresa Jack, Lisa Peers, Journey Among Women |

A 'Complicated Legacy'?

Journey Among Women was a controversial film in its time, and it continues to provoke debate and discussion. The Vienna Film Museum's program indicates something of its 'complicated legacy', referring to the film as a 'borderline case...a wild, feminist historical piece'. SBS's film reviewer, Simon Foster (2009), also suggests the film has been difficult to categorise in his Journey Among Women Review, A brutal, lost Australian classic:

"Journey Among Women is the black sheep of the family. Insanely uninhibited, the convict survival story is too steeped in graphic nudity and violence to sit alongside critic's darlings like My Brilliant Career (1979), Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975) or The Getting of Wisdom (1978). But it is also too artistically and intellectually noteworthy to be embraced by the genre B-movie aficionados."

In 1976 I was one of two camera assistants on the film and I shared a desire, along with other participants, to be involved in an emancipatory film project about women and freedom. As camera assistant I saw every moment flowing into the camera; yet in the end I witnessed a film that seemed to lean more towards the 'Ozploitation' genre. This is perhaps the film’s 'complicated legacy'. Yet perhaps the contributions of the feminist and professional actors, the co-writer, and the director's original intention, bring an embedded layer of ‘real’ revolt and jouissance into the text, beyond any surface performativity or actual sexism?

|

| Camera assistant, Jeni Thornley, Journey Among Women, Super8 screen shot |

In 1970s Australia the women's liberation movement was in full swing, and so the historically true stories of convict women of the 1820-30s, overthrowing their male captors to escape prison and seek freedom in the bush, had potent and mythic resonance. Director Tom Cowan was attuned to this zeitgeist and involved Dorothy Hewett – libertarian, feminist poet, novelist and playwright – as co-scriptwriter. Then he cast the convict women, quite intentionally, from amongst local radical feminist lesbians (some from Clitoris rock band) with professional women actors from the mainstream industry. He combined this with a 'psycho-drama' workshopping approach.

|

| Jude Kuring, Di Fuller, Journey Among Women |

Camped out in the bush, eventually this potent mix exploded when several cast members refused to perform in 'sexist' shots (being naked after the escape). The cooks downed tools, and me too. The breakdown in filming evolved into a sit-down discussion of all cast and crew. This was filmed, but not included in the final film.

|

| Nell Campbell, Lisa Peers, Journey Among Women |

Does the term, 'wild feminist historical piece' suit this film? In my view, (influenced by Claire Johnston's 1973 Notes on Women's Cinema), a feminist film is when women creatively participate in the development, production and distribution of a film, sharing authorship. In Journey Among Women, the film's gaze, its desire, was in the director and producer's hands; it was their gaze, not the women's gaze; yet, with such a complex film set, was there ever one unified group of women who could have delivered a women's gaze?

|

| L-R Nell Campbell, Robyn Moase, Tom Cowan, Rose Lilley, Peter Gailey, Jeni Thornley, Journey Among Women |

Debates around the film reverberate into the current #metoo movement today. One of the youngest of the Journey Among Women actors, whose role involved being raped in the convict cell, spoke at the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse in 2015 (in reference to the 'Entertainment Industry'). She included her experiences and her 'partially nude (topless) appearances' as part of her discussion.

|

| Uni of SA 2018 |

A Betraying Camera?

Film scholar, Jane Mills, in an essay for the 2009 DVD release of the film, 'Journey Among Women: Special and Electric', discusses the film through the prism of a 'betraying camera'. I find it a most thoughtful essay and was pleased that the producers had commissioned it for the DVD, as Mills' incisive contribution suggests they, too, recognised the film's complex legacy. Mills' writes:

"Betrayal is the theme that keeps rising to the surface in this extraordinary film. Did the director, producer and cinematographer betray the women cast and crew members? Were the women divided amongst themselves, as was rumoured, with the lesbian and radical separatist and the non-separatist women each feeling themselves betrayed by the other group or by women who crossed from one group to another? If you look closely you can see all these questions as well as the answers. By placing betrayal at the centre of concern, Journey Among Women reveals the diversity of ideas and opinions among the cast and crew. What is fascinating is that these fissures can all be seen inside the film's frames."

|

| Jeune Pritchard, Journey Among Women |

Outside the film's frames – "the charge of the real"

In 2016 the National Film and Sound Archive (Canberra) acquired and digitised my personal Super8 collection (1976-2003). Of 143 rolls, about 13 rolls were filmed on Journey Among Women. Some of this footage I used in my film Maidens back in 1978 to represent my own intense experience of utopian liberatory feminism, in part catalysed on the set of Journey Among Women in 1976.

|

| Christina Sparrow, NFSA Film Services, 2016 grading the Journey Among Women Super8 |

In a recent essay (2018) I suggest that this kind of intertextuality, juxtaposing fictional excerpts into the documentary mode (or vice-versa) produces what documentary theorist Stella Bruzzi refers to as "the charge of the real" (quoting film scholar Vivian Sobchack, 1997). Now we read fiction as documentary evidence – striking in its affect. In fact, my film practice always involves re-cycling images and scenes from my super8 collection in each film: Maidens, For Love or Money, To the Other Shore and Island Home Country. My current project memoryfilm, (in post-production) is constructed entirely from my 143 rolls Super8 collection. It's interesting, too, that in my documentaries (above) the journey towards liberation continues to unfold as a theme.

In the collaborative feature documentary For Love or Money (McMurchy, Nash, Oliver, Thornley 1983) we juxtaposed the Journey Among Women prison cell-escape scenes, with my Super8 of the wall of the Female Factory in Parramatta, to represent an actual revolt by convict women in 1827. Later in the film we used my Super8 footage of the 1983 Anzac Day March, when the Sydney Women Against Rape Collective was denied the right to march under their banner, "In memory of all Women Raped in all Wars". I filmed the women bravely marching direct into the police paddy wagons.

|

| Sydney Women Against Rape Collective, Anzac Day March, Sydney 1983 |

The closing scene of For Love or Money uses a close-up of one of the protestors from this Super8 footage. She gazes direct into the camera just before she is arrested, with narration from Dorothy Hewett's 1958 novel Bobbin Up, narrated by actor Noni Hazelhurst:

"She'd seen women fight, she'd seen them unite, she'd seen them show courage and resourcefulness. Give them a clear issue and they cut right through to the bone of it and stood solid as a rock."

|

| Anzac Day "We Mourn all Women Raped in all Wars", Sydney 1983 Super8 screen shot |

Postscript

Michele Johnson 1952-2019 Actor

References

Simon Foster (2009), Journey Among Women Review, A brutal, lost Australian classic, SBS Reviews, 7th December.

Jane Mills, (2009), 'Journey Among Women - Special and Electric': booklet accompanying Collectors Edition DVD, Journey Among Women, Umbrella Entertainment.

Claire Johnston (1973), Notes on Women's Cinema, London, Society for Education in Film and Television.

Benjamin Law and Beverley Wang (2019), 'Going beyond the hashtag with Me Too founder Tarana Burke', Stop Everything, ABC Radio National, 15th November 2015.

In 2017 I went to a screening of Journey Among Women (Q/A with Tom Cowan and John Weiley) during Sydney's annual Vivid Festival. It was part of a community film event on the top floor of a well known Kings Cross pub. It was a good night and the audience really appreciated the film. I felt more fondly towards the film (40 years later), being much less in the 1970s feminist rage part of my mind and now appreciating the complex multi-layers of this film. Later I wrote:

"Let's also honour Dorothy Hewett who wrote the screenplay with Tom Cowan and John Weiley. Watching the film, I could sense Dorothy's mind at work and the women actors intense contributions; I really valued the film more than I ever have – rather more as a documentary archive, if you like, than a drama."

Recently, while writing this article, I read an interview with Tom Cowan on the making of the film which helped me understand his original intention more keenly. Tom says:

"I was living in the bush, in Berowra Waters, and it was so powerful. I happened to read this French science-fiction story called Les Guérillères (Monique Wittig 1969) about a future society of women - like an Amazon society - who were at war with the rest of society. Somehow in the combination of the wildness and strangeness and beauty of the bush and this story of wild women, I saw a parallel in how we perceived the bush and how the British first saw the bush as ugly. Well, we now see it as beautiful. And how the sort of excesses of radical feminism, when it began, were seen as ugly - ranting and raving and being abusive and so on. But, in fact, behind it were very beautiful things - not just the women, but the humanist ideas."

In Memoriam Rest in Peace – cast and crew members

Dorothy Hewett 1923-2002

Co-Writer Journey Among Women

|

| Dorothy Hewett and Tom Cowan on location Journey Among Women |

Norma Moriceau 1944-2016

Costume Designer Journey Among Women

|

Jeune Pritchard, Norma Moriceau, Journey Among Women

Super8 screen shot

|

Michele Johnson 1952-2019 Actor

Journey Among Women

|

| Michele Journey Among Women Super8 screen shot |

References

Luke Buckmaster (2015), 'Journey Among Women rewatched – savagery in racy revenge drama', The Guardian, 20th December.

Simon Foster (2009), Journey Among Women Review, A brutal, lost Australian classic, SBS Reviews, 7th December.

Jane Mills, (2009), 'Journey Among Women - Special and Electric': booklet accompanying Collectors Edition DVD, Journey Among Women, Umbrella Entertainment.

Claire Johnston (1973), Notes on Women's Cinema, London, Society for Education in Film and Television.

Benjamin Law and Beverley Wang (2019), 'Going beyond the hashtag with Me Too founder Tarana Burke', Stop Everything, ABC Radio National, 15th November 2015.

Dr. Jeni Thornley

Hon Research Associate

School of Communication

Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, UTS

http://www.jenithornley.com/

mb 0414 9908951